02- Trailblazer Basics

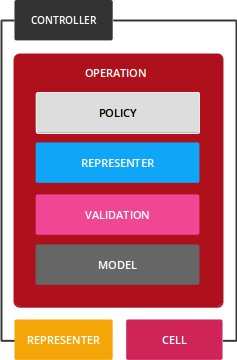

Last updated 06 June 2017 trailblazer v2.0Being able to populate the pipe, or railway, of an operation and handle errors, we now dive into the Trailblazer gem and the abstractions it gives us: persistence handling, validations, policies, and all that.

An importance architectural decision here is that most abstractions are implemented in completely separate gems. Those gems don’t even know they’re being used in a Trailblazer operation.

Instead of shipping with tons of code to implement forms or policies, Trailblazer provides glue code that mediate between the operation (flow control and specific customization) and the additional abstractions (validations, persistence, etc.).

This happens in macros, and we will learn a lot about those in the following session.

The Challenge

Coming back to the controller from chapter 01, I want you to quickly get an idea of what we’re trying to achieve now.

class BlogPostsController < RubyOnTrails::Controller

before_filter :authorize_user!

def create

post = BlogPost.new

post.assign_attributes(params[:blog_post])

if post.save

notify_current_user!

else

render

end

end

end

This is a classic Rails controller setup. Check if the user is authorized, create a model, validate the incoming parameters, if successful, save and notify the current user about it.

We’re going to rebuild this with a Trailblazer operation. We’re also going to do that without any infrastructure framework, such as Rails or Hanami. This is content for the following guides.

Code for this session is here.

WAT

Trailblazer is suitable both for greenfield projects as well as refactoring massive and messy legacy projects. The mechanics are always the same.

- Extract domain logic from controller, models and half-baked service objects and rearrange them embraced by an operation.

- Free the model: Validations go to forms (or contracts as we also call them).

- Callback code is triggered from the operation, not the model or controller.

- Authorization happens in policies orchestrated by the operation, not in random places in controller, model, or view.

You will see, it’s actually quite simple to let the operation control the flow and other stakeholder objects implement the specifics.

Gemfile

Have a look at the Gemfile.

gem "trailblazer"

gem "activerecord"

gem "sqlite3"

gem "rspec"

gem "dry-validation"

The trailblazer gem brings the operation, the Reform gem for contracts, and some code for the macros we’re going to discuss.

We already discussed rspec’s role. Mentioning the activerecord gem is important, since we need a persistence layer. Please be advised, though, that Trailblazer is database-agnostic: you can use ROM, Hanami::Model, Sequel, or whatever else you feel like.

For validations, we refrain from using ActiveModel::Validation in this example and use the excellent dry-validation gem. Reform allows using dry-v out-of-the-box. In case you want to/have to use ActiveModel’s validations, no problem, Reform does that, too.

Model

Since we’re going to create a new blog post record, it’s a good idea to add a model class. I put that in app/models/blog_post.rb.

class BlogPost < ActiveRecord::Base

end

This is an empty model that skips all the features of ActiveRecord’s that should’ve never been added, and leverages what ActiveRecord is amazing at: persistence.

We also have a User model, which is a simple Struct that allows us to set a signed_in? flag. In later chapters we will use a “real” user model and an authentication gem.

Procedural Approach

To implement the above controller action in an operation, you could simply throw the code into a single step, ignoring all the nice mechanics and error handling that comes with the pipe, but making it “understandable” to a new developer.

For illustration purposes, this Create operation goes to app/concepts/blog_post/operation/create.rb.

require "trailblazer"

class BlogPost::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step :do_everything!

def do_everything!(options, params:, current_user:, **)

return unless current_user.signed_in?

model = BlogPost.new

model.update_attributes(params[:blog_post])

if model.save

BlogPost::Notification.(current_user, model)

else

return false

end

end

end

The operation now orchestrates model, validation and the notification “callback” that used to sit in the controller. Note that no HTTP-related code, like redirects or rendering results, is found here anymore. That’s a step forward in our quest to separating concerns!

Procedural Approach: Test

A quick test makes sure that our authorization kicks in and an anonymous user leads to a failing operation, and no model is persisted.

require "spec_helper"

require_relative "../../../../app/models/user"

require_relative "../../../../app/models/blog_post"

require_relative "../../../../app/concepts/blog_post/operation/create"

RSpec.describe BlogPost::Create do

let (:anonymous) { User.new(false) }

let (:signed_in) { User.new(true) }

let (:pass_params) { { blog_post: { title: "Puns: Ode to Joy" } } }

it "fails with anonymous" do

result = BlogPost::Create.(pass_params, "current_user" => anonymous)

expect(result).to be_failure

expect(BlogPost.last).to be_nil

end

We also test the successful case here. It’s obvious that our current implementation is not great, for example, we don’t have access to the created model without manual work, which we don’t favor, do we?

Dependencies

Even though this operation is far from ideal, it demonstrates a very important concept in Trailblazer. Have you noticed how we pass in and access the current user?

There is no global state in Trailblazer, everything you need in the operation needs to go in via call.

The first argument is usually the framework’s params hash as discussed here. The second argument can be any hash specifying the dependencies needed in the operation, such as the current user.

result = BlogPost::Create.(pass_params, "current_user" => signed_in)

By passing the current user with a string key, you will be able to access it via options in all steps. And, of course, you as the attentive reader still remember that you can use keyword arguments to grab that current user (or whatever else you need from the options) in a local variable.

def do_everything!(options, params:, current_user:, **)

return unless current_user.signed_in?

Here’s what to remember about dependencies in a snapshot.

- Every dependency needs to go in via

call, whether that is in a controller, a test, or a background job. - Use required kw args wherever you can, as they will automatically raise an exception should the required keyword be absent.

Exposing Values

Before breaking up this monolith into small, flexible steps, it’s a good time to learn how we can communicate values to the caller via the result object. You remember, in our specs, in order to grab the model for specing, we had to use BlogPost.last - which yields potential for bugs.

Instead, we can simply write values to the options object. Those will be accessable to all following steps, as we’ll see in a few seconds.

def do_everything!(options, params:, current_user:, **)

return unless current_user.signed_in?

model = BlogPost.new

options["model"] = model # readable in steps and result.

model.update_attributes(params[:blog_post])

# ...

end

Writing to options will also allow to read that very value in the result object, allowing us to change the specs slightly.

it "fails with anonymous" do

result = BlogPost::Create.(pass_params, "current_user" => anonymous)

expect(result).to be_failure

expect(result["model"]).to be_nil

end

We can now test against result["model"] and retrieve the actual processed model instance.

Manual Steps

While all this works fine, we actually don’t need an operation for this procedural piece of code. We could put that in one of the “service objects” that spook through many Ruby applications out there.

Splitting up the procedural logic into steps will give us a better code structure and automatic error handling. Going further, using Trailblazer macros instead of manual steps, we will maximise stability and get helpful statuses in the result object.

class BlogPost::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step :authorize!

step :model!

step :persist!

step :notify!

def authorize!(options, current_user:, **)

current_user.signed_in?

end

def model!(options, **)

options["model"] = BlogPost.new

end

def persist!(options, params:, model:, **)

model.update_attributes(params[:blog_post])

model.save

end

def notify!(options, current_user:, model:, **)

BlogPost::Notification.(current_user, model)

end

end

Four steps now implement the exact same that we did in one procedural step. As you can see, error handling and ifs disappeared because if a step returns a falsey value, the remaining steps will be skipped. I also advise you to take a minute and check out how we use different kw args per step - this is such a helpful feature, you should use it and understand it.

The specs we wrote still pass, so we’re good to go to the next step.

Policy

One big advantage of Trailblazer’s Policy macro over our home-made authorize! step is: It will add its outcome to the result object, making it extremely simple to track what went wrong should things go wrong.

The other benefit of using this macro is: You don’t have to use the primitive guard implementation, but use your existing Pundit-style policies to intercept unauthorized users.

For simplicity, let’s go with the Guard macro for now.

class BlogPost::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step Policy::Guard( :authorize! )

step :model!

step :persist!

step :notify!

def authorize!(options, current_user:, **)

current_user.signed_in?

end

def model!(options, **)

options["model"] = BlogPost.new

end

def persist!(options, params:, model:, **)

model.update_attributes(params[:blog_post])

model.save

end

def notify!(options, current_user:, model:, **)

BlogPost::Notification.(current_user, model)

end

end

Check line 2. Guards are a good way to quickly implement access control, but I advise you to invest some time in a separated policy implementation such as pundit.

All Policy macros will leave a trace in the operation’s result object. Here’s the test snippet for anonymous users who will be declined.

it "fails with anonymous" do

result = BlogPost::Create.(pass_params, "current_user" => anonymous)

expect(result).to be_failure

expect(result["model"]).to be_nil

expect(result["result.policy.default"]).to be_failure

end

In other words: every Policy macro creates its own result object within the operation result. With Guard, you can only ask for validity.

result["result.policy.default"].success?

However, with Pundit policies, additional messages will be accessable via this “nested” result object. This is a great way to find out what happened in the operation should you get an unexpected invalid result.

Model

Trailblazer also has a convenient way to handle model creation and finding. The Model macro literally does what our model! step did.

class BlogPost::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step Policy::Guard( :authorize! )

step Model( BlogPost, :new )

step :persist!

step :notify!

def authorize!(options, current_user:, **)

current_user.signed_in?

end

def persist!(options, params:, model:, **)

model.update_attributes(params[:blog_post])

model.save

end

def notify!(options, current_user:, model:, **)

BlogPost::Notification.(current_user, model)

end

end

This shortens our code even more, and reduces possible bugs. Of course, Model can also find records as we will discover in the next chapter.

Note that Model is not designed for complex query logic - should you need that, you might want to write your own step, use a query object or even combine both in a macro. Also, you can maintain multiple models, should you require that.

The specs still pass, as we haven’t changed public behavior.

Contract

As a next step, or better, as next steps, we need to bring the validation into the operation. Remember, in Trailblazer, you don’t want validations in the model or the controller. These go into contracts.

Contracts are basically validations, and they can be simple callable objects you write yourself, or Dry::Schemas, or, as in this example, Reform objects. Luckily, the Contract macros make dealing with contracts (or forms, it’s the same!) very simple.

require_relative "../contract/create"

class BlogPost::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step Policy::Guard( :authorize! )

step Model( BlogPost, :new )

step Contract::Build( constant: BlogPost::Contract::Create )

step Contract::Validate( key: :blog_post )

step :persist!

step :notify!

def authorize!(options, current_user:, **)

current_user.signed_in?

end

def persist!(options, params:, model:, **)

model.save

end

def notify!(options, current_user:, model:, **)

BlogPost::Notification.(current_user, model)

end

end

As you can see, we added two steps after Model, and reduced the logic in persist! to saving the model. This code will break, but it’s great to show you some mechanics with contracts, so bear with me.

Build

The first new step is Contract::Build.

step Contract::Build( constant: BlogPost::Contract::Create )

Even though Trailblazer allows to have “inline contracts”, we don’t want to clutter our operation with additional validation code. This is why I use the :constant option to tell Contract::Build what contract class to use.

Don’t try to understand everything at once right now, just believe me that Contract::Build will create this mysterious contract class and pass it the operation’s model.

Have a look at this contract in app/concepts/blog_post/contract/create.rb.

require "reform"

require "reform/form/dry"

module BlogPost::Contract

class Create < Reform::Form

include Dry

property :title

property :body

validation do

required(:title).filled

required(:body).maybe(min_size?: 9)

end

end

end

Without going into too much detail about contracts (they have their own guides), it’s obvious that this contract defines its fields with property and then uses dry-validation’s specific DSL to create a validation chain.

validation do

required(:title).filled

required(:body).maybe(min_size?: 9)

end

We simply define title as a required field, which must not be blank. Also, the body might filled, and if it is, it should be 9 characters minimum. Dry-validation needs a few minutes to sink in, but then it is so much more powerful and readable than the outdated ActiveModel::Validations.

The Build macro will always pass the operation’s default model to the contract constructor and save the contract instance in options. What goes on here is this.

# pseudo code

Contract::Build()

options["contract.default"] = BlogPost::Contract::Create.new(options["model"])

Again, no need to understand this right now, should you be unexperienced with Reform. We will go that at a later point.

For those who know Reform: after Contract::Build, you always have the contract instance in options["contract.default"].

Validation

Now, whatever building the contract implies, how do we run that validation against the incoming parameters?

Here’s a passing spec snippet.

result = BlogPost::Create.(

{ blog_post: { title: "Puns: Ode to Joy", body: "" } },

"current_user" => signed_in

)

In the test case, we pass in a manual hash to call, but in, say, a Rails app, this would be the params hash. This input is now validated via the Contract::Validate macro.

step Contract::Validate( key: :blog_post )

Again, Reform’s API will be utilized here by Trailblazer. We discussed earlier that the operation is only an orchestrator, knowing how to operate abstractions such as the contract, but having no further knowledge of how they work.

What Contract::Validate will do at run-time could be expressed as follows.

# pseudo code

Contract::Validate( key: :blog_post )

reform_contract = options["contract.default"]

result = reform_contract.validate(options["params"][:blog_post])

In a nutshell, Trailblazer uses the contract’s validate method, passes in the fragment from the params hash you provided, and lets Reform sort out validations, generating error messages and providing an actual result for us. If that fails due to insufficient input, Contract::Validate will deviate to the left track and no further steps will be executed.

It is incredibly important to understand the :key option here. Validate will extract the blog_post: fragment from the params hash, if you provide the :key option, and it won’t continue if it can’t find this key.

Omitting :key, Validate will try to validate the entire params hash, which is fine if you don’t use wrappers. However, frameworks like Rails and gems such as simple_form always add this wrap, so be wary.

Also, please note that Reform’s validation takes away the need for strong_parameters. Since all desired input fields were declared using property in the contract, it can simply filter out other irrelevant keys.

property :title

property :body

You don’t need strong_parameters with Trailblazer.

Errors

Let’s play a bit with different input for our operation to learn how errors can be extracted from the result object.

In the first spec, we completely fail to provide any sensible input.

it "fails with missing input" do

result = BlogPost::Create.({}, "current_user" => signed_in)

expect(result).to be_failure

end

Here, the blog_post: fragment in the params hash is completely missing, the validation is not even triggered. That is, because the extraction of the blog_post: fragment fails, which leads to a failed operation without any error message.

In upcoming versions of TRB, this specific failure will be indicated better.

The next spec sends a body with the wrong length - it must be more than 9 characters long. Why, we don’t know, but the business asks for this validation.

it "fails with body too short" do

result = BlogPost::Create.(

{ blog_post: { title: "Heatwave!", body: "Too hot!" } },

"current_user" => signed_in

)

expect(result).to be_failure

expect(result["result.contract.default"].errors.messages).to eq(

{:body => ["size cannot be less than 9"]} )

end

By inspecting the contract’s errors object, we can assert that our validations work. It’s usually best to test the error messages to see if and what validations were triggered.

We are working on trailblazer-test that will provide matchers for Minitest and Rspec to have less verbose tests.

Trailblazer tries to abstract the Reform or dry-validation internals from you, so you can always access the contract’s result field in the result object for errors and state. This also works pretty well when using form builders, which we will see in the next chapter.

Persist

When running our to-be-successful test case, whatsoever, it still breaks.

it "works with known user" do

result = BlogPost::Create.(

{ blog_post: { title: "Puns: Ode to Joy", body: "" } },

"current_user" => signed_in

)

expect(result).to be_success

expect(result["model"]).to be_persisted

expect(result["model"].title).to eq("Puns: Ode to Joy") # fails!

end

The error message here will give us some hint.

Failure/Error: expect(result["model"].title).to eq("Puns: Ode to Joy") # fails!

expected: "Puns: Ode to Joy"

got: nil

Apparently, the operation’s BlogPost model got persisted, but it’s empty. No attributes were assigned, even though they were valid.

This is because when validating the input, this all happens in the contract. Values to-be-validated are written and checked on the contract instance, not on the model. The model is not touched until we say so.

In other words: what we need is to push the validated data from contract to the model, and then save the model. This can be done with the Contract::Persist macro.

require_relative "../contract/create"

class BlogPost::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step Policy::Guard( :authorize! )

step Model( BlogPost, :new )

step Contract::Build( constant: BlogPost::Contract::Create )

step Contract::Validate( key: :blog_post )

step Contract::Persist()

step :notify!

def authorize!(options, current_user:, **)

current_user.signed_in?

end

def notify!(options, current_user:, model:, **)

options["result.notify"] = BlogPost::Notification.(current_user, model)

end

end

Replacing our own step, Persist will use Reform’s API to push the data to the model. In pseudo code, this is what takes place.

# pseudo code

Contract::Persist( )

reform_contract = options["contract.default"]

reform_contract.save

The contract’s save method does exactly that for us, plus it saves the model.

And… our tests pass!

BTW, another nice thing is: if the model’s save returns false, this will also result in the pipe jumping to the left track, skipping our last step notify!

Notify

Speaking of notify!, this is the last step we need to review, and then you can call yourself a Trailblazer expert. In the current state of our application, Notification is just an empty class doing nothing.

To conclude this chapter, I would like to keep it that way. A dedicated guide will talk about post-processing logic (callbacks), testing and mocking external services like mailers with dependency injections.

Summary

You’re now ready to write full-blown operations implementing the entire workflow for a function of an application. Even though you could do all the steps yourself, the TRB macros help you in doing so.

There might be open questions around contracts, but we will discuss them in a separate guide. If you can’t wait for it, have a look at the Trailblazer book, page 51 et seq. explain Reform in great detail.

In the next chapter we will discover how to use operations in Rails, where HTML forms get rendered and send input to endpoints. Exciting stuff!